As an assistant professor who likes to talk about financial happiness and as a financial planner who has a practice focused on academics, I am often surprised by how little effort goes into planning our financial lives. We are all smart people, we know a lot about everything from 18th-century opera to asset pricing, and somehow, we don’t prioritize the conscious financial aspect of our lives. So here is some money-related advice for the recent-ish graduates who have left their impoverished Ph.D. lives and moved on to the relatively free-flowing cash world of the professorship.

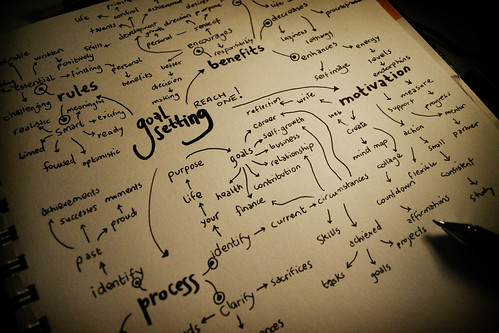

1.Think about what is important to you before money starts pouring in. The transition from Ph.D. student to assistant professor/instructor comes with a nice monetary benefit. What I have observed so far in many academics is that lifestyle, needs, and desires will adjust really fast to the new paychecks. While before we were making ends meet on the $18k stipend, now $75k does not seem enough. My advice is: take a deep breath, write down your life goals, figure out how much money you really need to be happy, and decide what you would like to spend your money on. The more intentional you are about your paycheck allocation, the less stressed you will be in the future. Repeat this exercise when you get promoted to associate and full professor. It’s actually something we should be doing before any increase in pay.

2. Take that 403(b), 457, or 401(k) seriously. This is an amazing benefit and many colleges are very generous when it comes to funding your retirement. Forget about the pension for a moment and focus on this portion of your retirement because this is the portion you can actually control. Even if you have a pension and your college does not match any 403(b) contributions, take some time and look into it. In an ideal world, every professor I know would max it out. I understand, however, that finding $18k in your budget is not the easiest thing, so just do your best. Put as much as you can aside into a non-pension retirement account. [Note: If you are not sold on why you should be putting this money away, please go to my website and sign up for the 5 emails that deal with the 403(b) allocation. It is such a big decision, it deserves your time].

3. Ask questions about your pension. In case your college still has a traditional pension plan (and many colleges do), put some effort into understanding it. Many of us take the pension either as a great benefit or something that is no longer going to be there when we retire (just like social security). The reality is somewhere in the between but unless you know the details of your pension, how it is calculated, and how well it is funded, it is really hard to understand what it means to you (and if you are in IL you probably already realized that it means a lot). There are so many resources out there; a little bit of time may mean the difference between deciding whether you will to stay at your current job or look for a new one. I just worked with someone who decided to quit her tenure track job and take an instructor position in a different state because of the much better pension.

4. Get to know the difference between the defined benefit type pension and the defined contribution type retirement. As far as academic benefits go- this is a really big one. Some schools do not give you a choice. For example, in the Cal State system, CALPERS is the only option available. However, many states and schools make you responsible for that choice and it is a one shot deal. If you feel like you can’t make this choice because you don’t know enough, get some help. This decision might potentially mean more to you than your actual salary. You do not want to leave this choice in the hands of the retirement gods.

5. Assess whether your current job is really the best for your living standard. This is a tough one. We are conditioned to fight for tenure and keep it once we get it. Leaving a job to move to a lower cost area is pretty radical. But money-wise, it can be such a big difference where you earn your paycheck. I live in Los Angeles; I just moved here because sometimes you need to follow your husband rather than your own financial advice and this one hurts me a lot. For every dollar I used to make in Florida, I need to make $1.9 in LA. That is $2 to $1, people. My salary certainly did not double when I moved to California. If you have a choice or if you got to a point in life where you can afford to be picky, thinking about how far your money goes in different states and cities is important. Here is a good comparison tool to play with: http://money.cnn.com/calculator/pf/cost-of-living/

6. Get a grasp on your student loans. A comparison analysis of your student loan options may save you money, lots of money. You do not have to pay what “the man” told you to pay. Very few Ph.D.s I know finished school without student loans (if you are one of those, good for you!) but for the rest of us, it may be time to start paying those student loans back. What you pay, in what order you pay it, and whether you pay it at all makes a difference. For example, I recently refinanced my federal student loans from 6.55% to a private lender at 1.95%. This was the best for me. I also just told my sister who is entering repayment that she needs to stretch her loans for the extended period because this makes more sense for her. We are both going to end up saving thousands of dollars but the way each of us got there, is very different. You need to figure out what is best for you and your student loans.

7. Think hard about buying a house when you move to a new job. I know we all want tips of how to get rich fast but after 3 houses in 3 states for 3 different academic positions, I am pretty sure buying a house is not it. Your expectation of how long you will stay in this job is very important, but so are many other factors. If you found a deal that is a cash maker (for example, a house where your mortgage is $1,600 and the rent income is $2,450), buy it even if you are not convinced you will stay in this job for longer than a year. However, if you are moving to San Francisco, are not sure about your tenure, and do not have a husband who owns Google, it may not be so wise to buy that $800k condo. This is another one of those decisions that may be worth thousands of dollars in either direction.

8. Negotiate your package. This is obviously applicable to someone who has just secured an offer. Once you are in your 3rd year, not much negotiation is possible. Remember that everything is negotiable, not just the salary. Deans are nice people (in most cases); they want to get the best person for the job. They usually do not hoard money for themselves but there is only that much room they have when it comes to salaries. [Note: Still- even if you get $2k more per year, over 30 years at the reasonable investment rate, you are looking at an extra $200k. It’s worth to ask.] However, you can also negotiate moving expenses, summer support (my favorite because there is more flexibility there), any special responsibilities (will you be the director of something and as such, can you get some more money?). When all else fails money-wise, you can also negotiate loads, preps, schedules, and even your parking spot (seriously, I know someone who did that although I wouldn’t recommend it; the dean had to give his spot up and will never forget that). One of the biggest shocks I experienced when moving from industry to academia is how little professors negotiate. This is your life, your salary, and you will be working very hard for it. There is no shame in asking for more.

9. Take advantage of your benefits. The package of academic benefits is usually pretty awesome. Unlike many other professions where you really can’t only rely on the employer benefits for everything, here you could be just fine doing nothing else but maximizing those benefits. But you do need to spend the time on them. I spent about 50-70 hours working on my benefits and making sure there is nothing else I can extract from my current job. I don’t advocate you do nothing else for a week, but try spend some time on this task. 30 minutes allocated towards your 403(b) is really sad, especially when you may be leaving hundreds of thousands of dollars on the table. Just take the time and try to figure it out.

10. Finally, please call a financial planner and get some basics covered. I am currently working on a paper looking at the 403(b) accounts of professors at a large US school. What I see makes me depressed. Please don’t be the person who chose the JP Morgan large cap fund for 1.11% when the Vanguard fund that does the same is right next to it and costs 0.05%. You should obviously call me for all your help but in case that’s not your cup of tea, make sure whoever you call is a fee-only (or at least fee-based) advisor. Do not get a commission person; that person gets paid for what she sells you and not the advice she provides. If you are interested in finding a good person, let me know and I will provide you some places to start with. These days, so many people offer a good financial analysis for really cheap (you can get a basic review for about $500), that it is a sin not to do it.

If you have any financial questions, please contact me. You can find all my information here: http://attainablewealthfp.com/contact/